BEAUTY CASE

Photography © Tonatiuh Ambrosetti

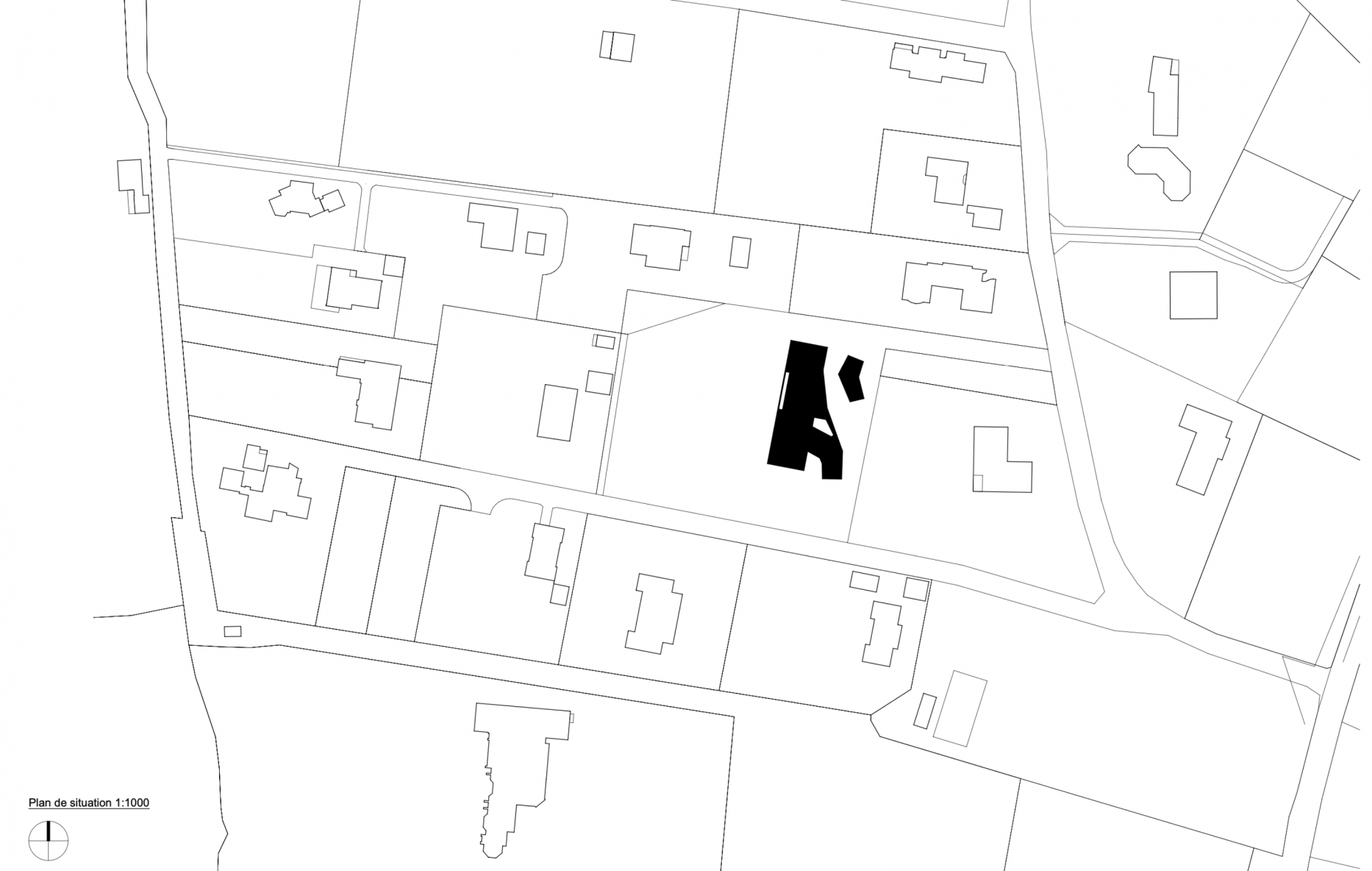

Built on an old orchard, this house has been made to measure. The set offers a feeling of serenity that is not contradicted by the majesty of the volumes, nor by the size of the rooms.

Assuredly, she is tall and luminous; she is obviously elegant; of course, it is in a quiet and beautiful place ... The list can stretch at length as the house has impressive features. But the exercise of an enumeration of standing attributes does not really interest to understand the building. At the same time richer and less anecdotal, its deepest identity remains tied to the history of a family, a site, and an era ours.

Legacy codes of the 18th and 19th century

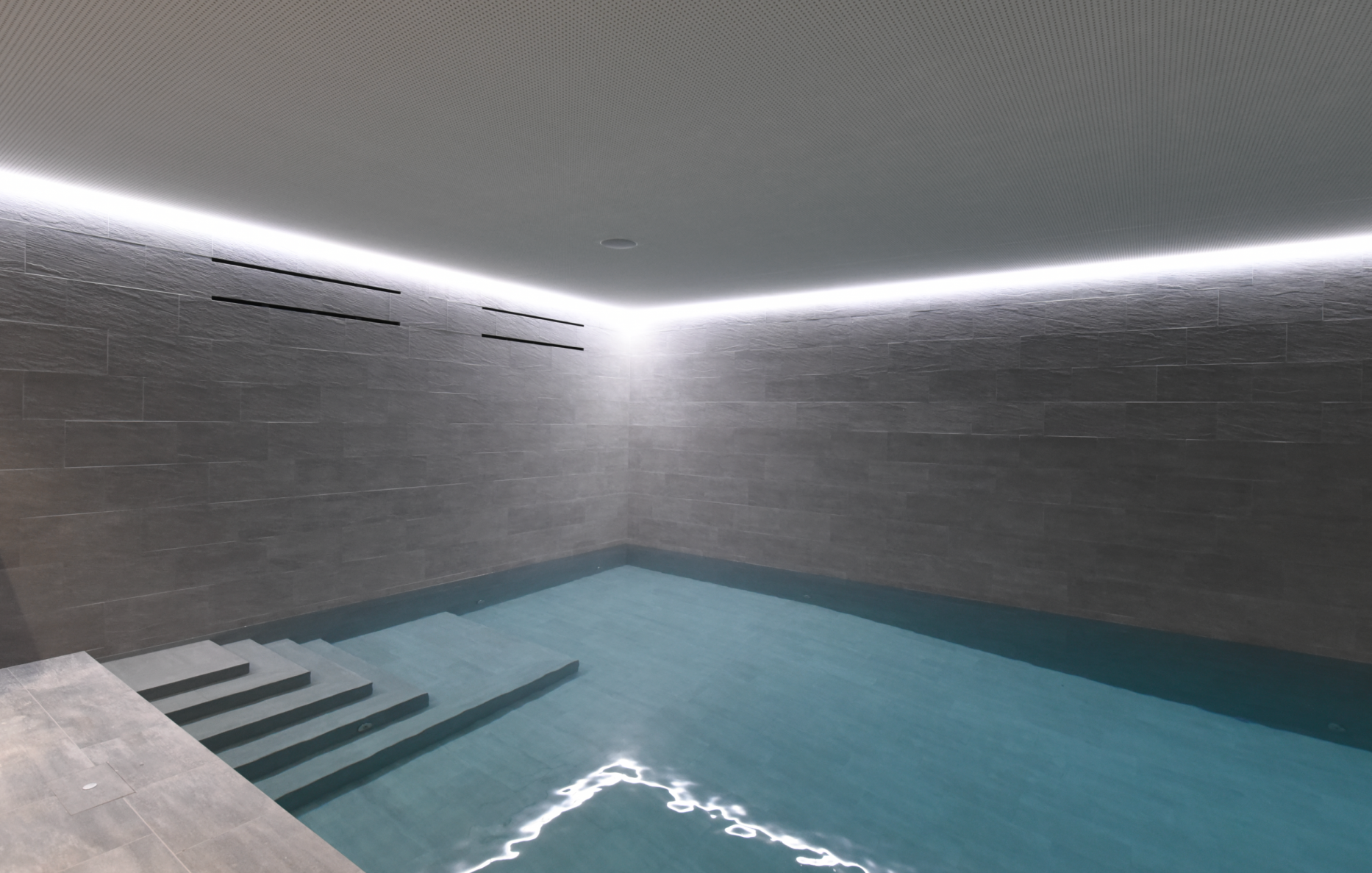

The program must consider individual needs and reflect on each individual's evolution. It must also satisfy the daily organization of the group, both in its private operation and in its broader social dynamics (receptions, dinners with friends, punctual accommodation). In many respects, needs refer to large private houses codified between the 18th and the 19th century. As in the mansions of the time, one finds the main entrance and a service entrance, generous staircases, enfilades, double heights, rooms made to receive, others to work or to relax. Day zones are clearly separated from night areas; spaces dedicated to sociability do not communicate with those reserved for the private sphere.

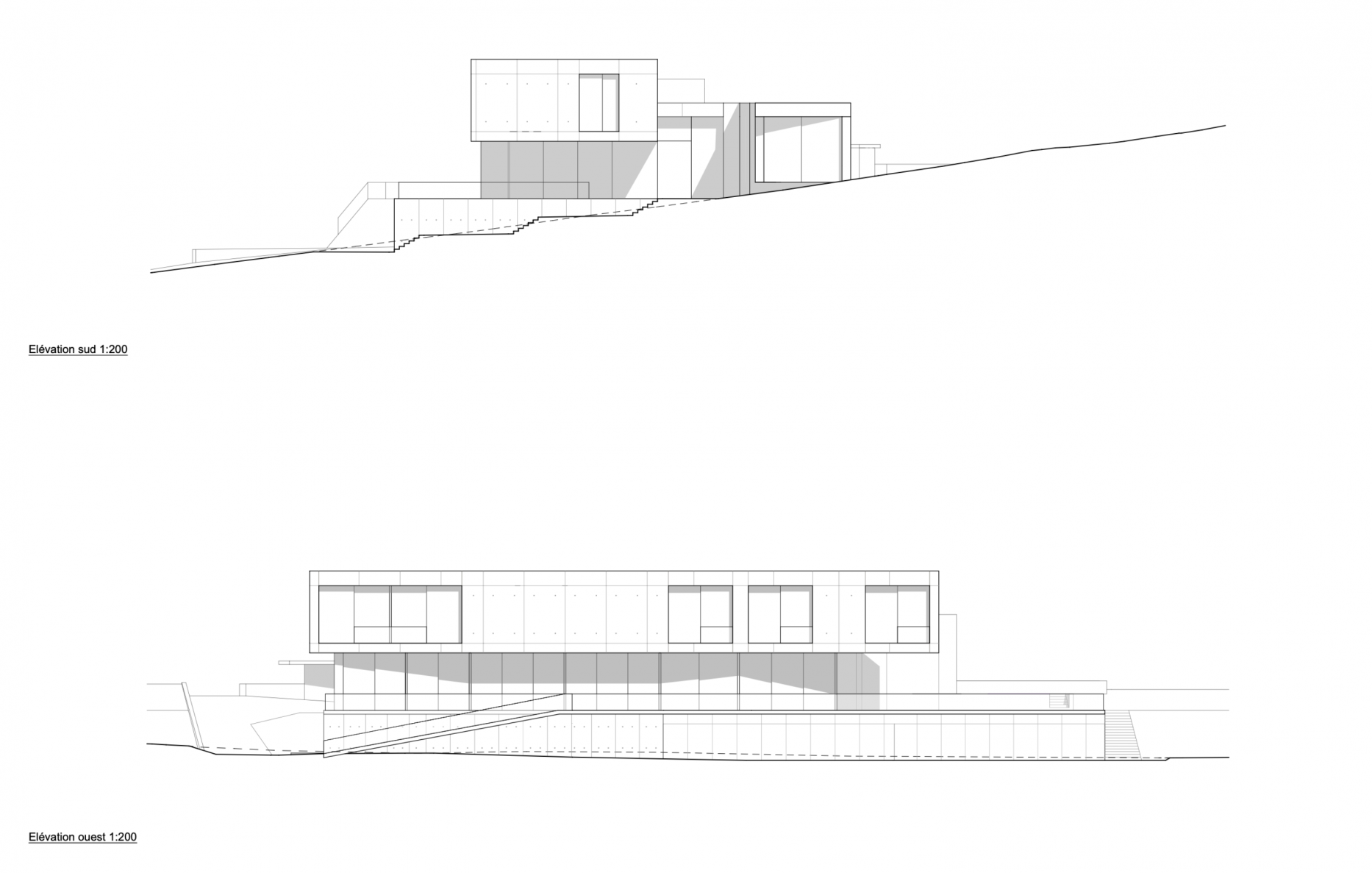

This classic typological program adopts a contemporary vocabulary, freed from the rules usually applied to this type of dwelling. Formal clarity, volumetric simplicity and great restraint in the choice of colors or materials, however, conceal an unsuspected constructive complexity. This is the case especially for rough concrete work whose regular moiré finish throughout the house has left no room for improvisation. The coordination between architects, engineers and companies have indeed allowed playing the imposing dimensions of walls or cantilevers, without compromising on the quality of implementation and without perverting the purity of the lines. In the same vein, many discrete options meet the highest standards of safety and comfort. The general spatial arrangement is not disturbed; the fineness of the details is not weighed down.

Marry the landscape

A sculptural object defined by clean surfaces and almost austere materiality, the house remains happily welcoming and convivial. The spaces connect with each other thanks to the short and fluid circulations, adapted to the daily use of the inhabitants; the whole offers a feeling of serenity that is not contradicted by the majesty of the volumes, nor by the size of the rooms. This warm atmosphere is particularly expressed around a kitchen thought of as the throbbing heart of the house. Designed at the family level, this dynamic place of life is organized in the south-west corner of the house. The orientation is ideal to enjoy the sheltered terrace, the beautiful opening onto the garden and, further, the release on the Léman. Mineral block placed on a glass slide, the front of the house allows the living rooms to surrender to the tranquility of the landscape. Rigid and severe, this geometry is softened on the rear to meet less formalistic needs while adjusting to the natural morphology of a sloping terrain. The relationship between the building and nature is established; the site has adopted the house.

INTERVIEW WITH FRANCESCO SNOZZI, ENGINEER AT INGENI

By jacques perret

When it comes to individual villas, the role of the engineer often remains somewhat in the shadow of that of the architect, whose ideas are only seen as being put into practice. However, the final appearance of the villa also owes a great deal to the group of engineers led by Francesco Snozzi.

Q1: Francesco Snozzi, how does the realization of this villa differ from traditional situations?

This project was indeed a great challenge for us, characterized in particular by the fact that not only the architects but also the client were very interested in structural issues. The owners really wanted to take advantage of our experience and know-how to design and build an exceptional object.

This interest was initially shown in a mini-competition held at the preliminary design stage. It was thanks to this that we were able to demonstrate our skills and the relevance of our approach to static issues, proposing solutions that integrated both architectural and structural requirements. The role of the owners was thus not limited to "validating" the choice of one engineering office among others, but they also made a point of actively participating in certain exchanges of views in order to understand our approach: they understood that in order to obtain the desired house, certain choices had to be made at the early stage of the studies. They had understood that, to obtain the desired house, certain choices had to be made at the first stage of the studies. They therefore agreed to make a few changes in the organization of the house, in particular a slight relocation of the walls on the first floor. This decision allowed them to balance the structure and optimize the resumption of efforts on the ground floor. And to make the impressive 12-metre overhang overlooking the terrace and kitchen possible.

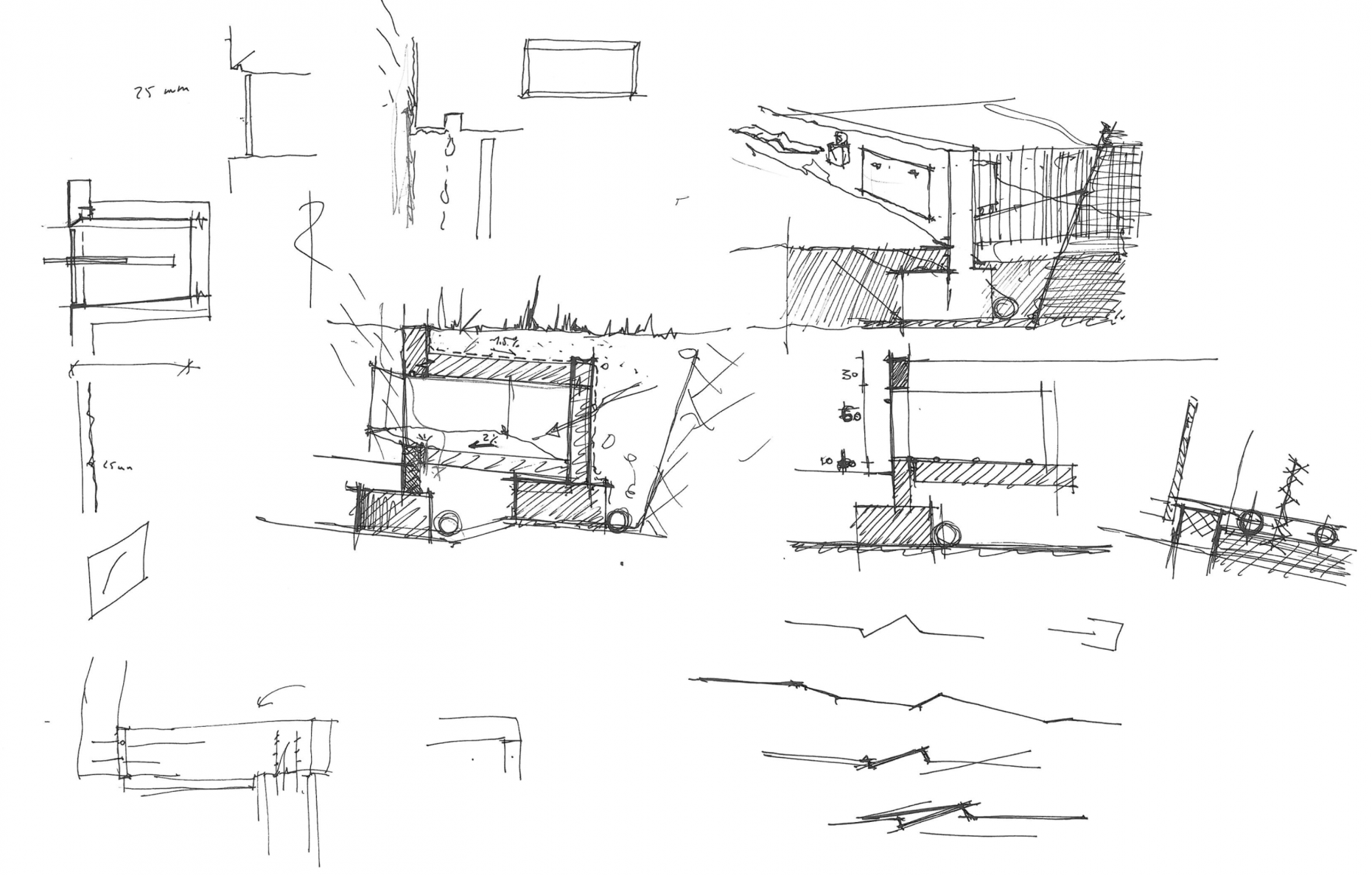

Q2: Tell us a little about this overhang: how does it work and what were the main constraints?

To begin with, I would like to say that this is not a simple structural performance, but a solution that concretizes an essential element of the architectural project: creating the illusion that the first floor is housed in a concrete box that "floats" above the ground floor. It should also be noted that, even though the span of some is small, the four sides of the box function as cantilevers. This contributes very strongly to the achievement of the architectural objective, which is particularly evident on the main facade facing the lake, where the concrete block seems to rest on a glass façade.

From a static point of view, it was initially planned to integrate one or more support points to support the bedrooms. In order not to affect the visual aspect, these hypothetical pillars were not foreseen in the front façade of the building, but in the removable glazing separating the kitchen from the terrace. Statically, they would have significantly reduced the magnitude of the overhang and the difficulties in managing the vertical deformations (arrows) that determine the tolerances of the glazing. However, these pillars would have been elements, so to speak, foreign to the rest of the structure, which would have undeniably hindered the expression of the architectural will.

In order to avoid these additional supports and to free up as much space as possible on the ground floor, we had the idea of stiffening the cantilevered part of the floor by using the inner walls and the gable wall as sails and by introducing prestressing cables. To achieve effective behaviour, the longitudinal wall separating the bedrooms from the corridor had to be shifted slightly towards the front of the house. This shifting allowed the loads to be centred and thus reduced the effects of torsion, ensuring uniform deformation of the overhang.

Indeed, the main problems were not related to resistance, but to displacement since the façade, entirely glazed and removable near the terrace, required good control of the deformation of the overhang. This did not prevent the construction detail for the connection between the façade and the ceiling slab from proving to be relatively complex, as the joint between the windows and the slab had to be adjusted during the decisive period of the concrete placement, i.e. five years.

Q3: The visual result owes much to the quality and placement of the concrete. On this subject, the layout of the façades has been carefully studied: the illusion is such that one does not perceive that the storey is supported from above and that one really has the expected vision of a slab laid on glass. How does one achieve such a result?

The layout was simply one of the tools among others that made it possible to achieve the final result: a perfectly homogeneous concrete parallelepiped floating on the ground floor. The choice of the type of formwork panels, their dimensions, the size, the thickness and the shape of the concrete slab was a key factor in the choice of the formwork.The combination of all these elements is the result of a very close collaboration not only between the architect and the engineer, but also with the contractor. At the end, a surface area of approximately 1,500 m2 of exposed concrete without any expansion joints, traces of cracks or variations in colour that are undeniably out of the ordinary.